Once upon a time spent many hours lying on my belly in the prairie counting and identifying the stems in little quarter meter square worlds. In the Flint Hills of Kansas, one of my most ubiquitous fellows was sun sedge, Carex inops ssp. heliophila, which was often only outnumbered in stem count by little bluestem or prairie dropseed (which were beasts to count). Usually by the time of my first sampling in May signs of flowering and fruiting had faded, but it could still be reliably identified by it’s pale green foliage relative to Mead’s sedge (Carex meadii) and long-rhizomatous nature…also the absence locally of very similar-looking Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica), of which it was once considered a variety (var. digyna).

I’ve been looking for sun sedge for eleven years now in Wisconsin, and it has not been easy, because Pennsylvania sedge is everywhere, and some floras give the field botanist little to by in terms of separating the two, in some cases it’s just a perigynium size cut-off, and in some of those cases it’s optimistically too small (1.5mm wide, when Pennsylvania sedge at the high end can be 1.7mm wide). Mature enough perigynia to assess are also only held on the plants briefly in late spring. Last spring I made targeted visits to some prairie remnants near an old collection site for sun sedge, and I came up empty…well one of the sedges on one of the prairies was probably it, but the perigynia were not yet ripe enough to make a slam dunk case.

Later last year I spotted a rhizomatous, vegetative sedge on a tour one of my favorite dry to dry-mesic prairies (nice because of very frequ]ent, very early spring burning…vs. middle April or after), and thought that it just might finally be sun sedge. I stopped by again in April to find the sedge flowering. I knew it when I saw it because there is a decent field character for separating sun sedge and Pennsylvania sedge apart from the perigynia, it’s foliage is held more stiffly erect, whereas Pennsylvania sedge has flexuous foliage. On top of that, the most distal staminate scales were relatively acuminate. So it was worth going back. …but I needed perigynia for proof, so I went back on 5/16 and hit it at the perfect time. Below are some images of sun sedge and contrasts with Pennsylvania sedge.

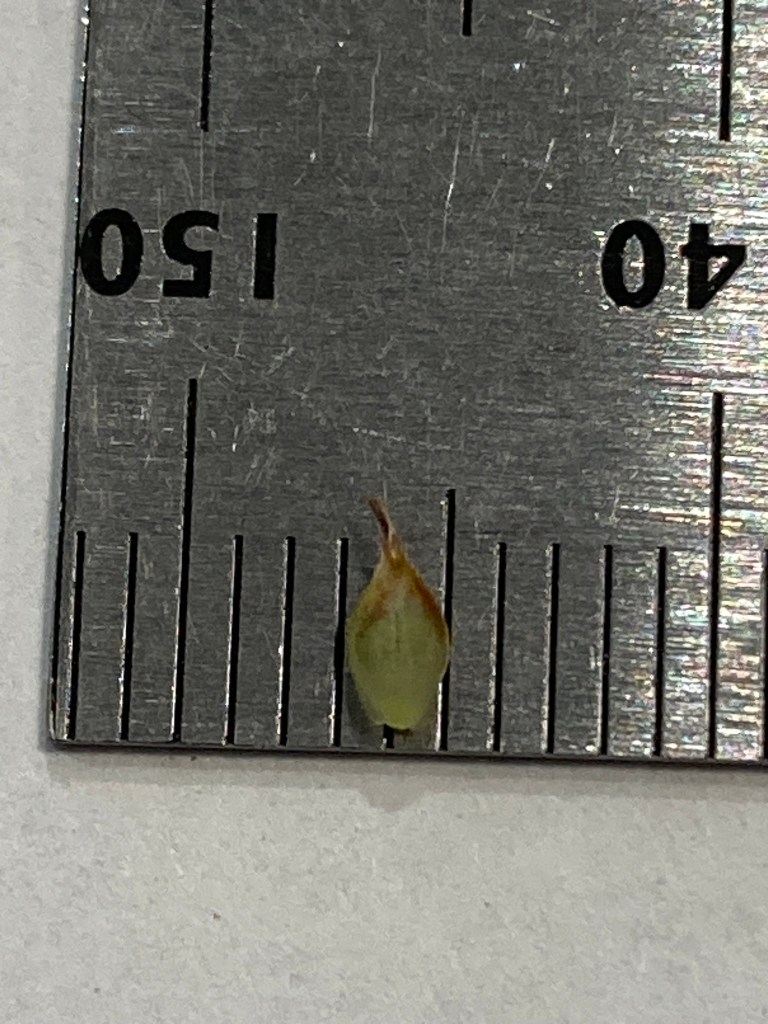

Sun sedge perigynium. The largest should be about 2mm wide or wider, especially considering there will be slight shrinkage upon drying (most keys are based on dried herbarium material). They will shink less width-wise than length-wise (maybe 1 tenth or two of a mm).

Mature (readily disarticulated) sun sedge perigynium top and Pennsylvania sedge (bottom). Note that this Pennsylvania sedge peryginium was 1.5-1.6mm wide, so perhaps ambiguous or misleading in some keys, but still narrower in measurement with a shorter beak (once any retained stigmas are knocked off).

Sun sedge is mostly a species of dry to dry-mesic prairies, meadows, and open savannas. Some woodland populations might persist with succession to more closed conditions. It occurs in a variety of soils, but eastward it is apparently more often in sandy soils. The spot where I located it was a mixture of sand and gravel (mostly dolomite). Pennsylvania sedge can be found in prairies too, but usually those in close proximity to historical savannas and woodlands, so sedges in historically wide open prairies deserve more scrutiny.

You must be logged in to post a comment.